Kubernetes and Docker Swarm are both popular and well-known container orchestration platforms. You don’t need a container orchestrator to run a container, but they are important for keeping your containers healthy and add enough value to mean you need to know about them.

This blog post introduces the need for an orchestrator then chalks-up the differences at an operational level between these two platforms.

Update – Docker now shipping Kubernetes

Update from Dockercon on 17th October – Docker are now shipping Kubernetes with Docker Enterprise Edition, Docker CE and Docker for Mac.

What has orchestration done for you lately?

Even if you are not using Kubernetes or Swarm for your internal projects – it doesn’t mean that you’re not benefitting from their use. For instance ADP who provide iHCM and Payroll in the USA use Docker’s EE product (which is based around Swarm) to run some of their key systems.

ADP’s Jim Ford told me: there are 600 nodes running EE with 40% of those in the production datacenters.

If you are a regular GitHub user – then behind the scenes the Kubernetes code is keeping things running for you. Read more: Kubernetes at GitHub

Here are some of the features these platforms enable:

- Clustering (computing power is bonded across multiple machines)

- Orchestration (the platform decides where code should run)

- High availability (more than one replica of your code running at once)

- Fault tolerance (if one of your replicas becomes unhealthy or crashes, it can be restarted automatically)

- Secret management (it becomes easier to share secrets securely between hosts)

So if you are running an application in production then you need to look into whether orchestration can help.

Chalk-board

Let’s chalk-up some of the differences between the two platforms.

Other projects are available such as: Rancher Cattle, Mesosphere and cloud-based i.e. EC2 container service / Azure Container Service. They are beyond the scope of this post but have similar concepts.

Distribution

Docker Swarm is packaged in two products – Docker CE (free and open-source) and Docker EE (for enterprise and business). Docker Swarm comes built into every Docker installation since Docker 1.12 and forms part of the main binary.

Did you know there was a pre-runner to Docker Swarm which was also called Swarm? Before Docker’s 1.12 release there was an earlier project called Swarm that existed as a separate set of binaries using Docker’s remote API.

Although many projects and components make up Docker’s Linux distribution it comes in just a few binaries: the client, the daemon and containerd. Internally it makes use of runc for spinning up containers and the SwarmKit project provides orchestration. The binaries are so small they can even run on a Raspberry Pi with 512mb of RAM.

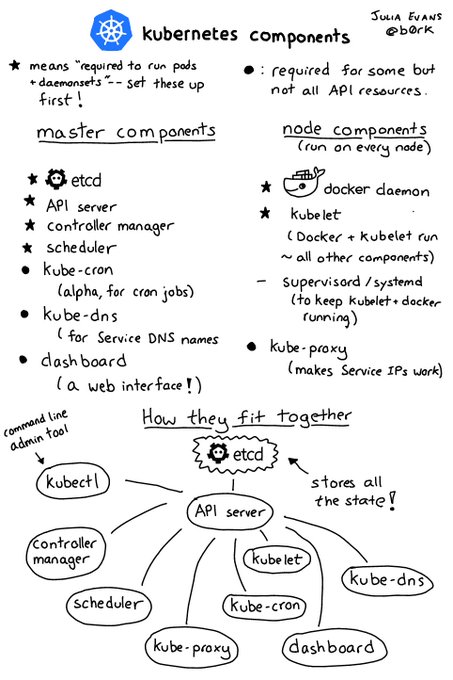

Kubernetes takes a different approach to system-building. It has a UNIX flavour in that it is separated out into a dozen separate projects which combine to become a distribution. An example would be the kubelet (runs containers), kubectl client CLI and apiserver which runs on hosts to provide access to the API.

See a diagram by Julia Evans on the internals of Kubernetes

Docker Swarm is a smaller distribution, included in Docker CE by default and has fewer moving parts. Kubernetes needs more resources, but can be composed of everything or just what parts of the system you need for a solution.

Primitives

For Docker the basic primitive was always a container, but with Docker Swarm we have the service which is a declarative configuration. The service says what state we need to be created by the cluster – then the cluster will try to make that happen. When a service creates a container it is called a task.

Groups of services are commonly placed on a custom overlay network and this can be made easier through the use of “Docker stacks” – the replacement for Docker Compose.

In Kubernetes we also have declarative configuration which can be specified on the command-line, or via a YAML file. The YAML format is more complex, but also more versatile – fortunately there are lots of examples in the documentation.

The basic unit of computation is the pod which is one or more related containers running on the same host, on the same network with access to each other – they may even share volumes. The pod concept can be very powerful when some initialisation code needs to run before a container can start.

Pods gain high-availability through deployments – this is similar to the Docker Service and has surpassed an older Kubernetes type called the ReplicationController. (Not to be confused with the lower-level “ReplicaSet” used as part of a “Deployment”)

Whether using a Deployment in Kubernetes or a Service in Docker Swarm – when your container crashes, becomes unhealthy or the node it’s running on goes offline – they will do the right thing to restore equilibrium.

CLI

Docker Swarm’s CLI is shared with Docker. There are two new namespaces important for Swarm:

Initialize/join a Swarm

docker swarm COMMAND

Docker also provides products which target different clouds such as Docker for AWS / Docker for Azure. See the store for more information.

Manage / list nodes:

docker node COMMAND

Create / manage / list Swarm services (container deployments)

docker service COMMAND

Commands can only be run directly on master nodes or if remote access over TLS has been set up on the master. The CLI is generally distributed with the whole Docker CE/EE package.

The Kubernetes CLI is called kubectl and is available via apt on Debian-based systems or through GitHub. Unlike with swarm – kubectl is only used for managing deployments and cluster configuration – it is not used to create a cluster.

To create a cluster – use a third-party tool like:

- kops – create a production cluster you manage on AWS

- GKE – create a production cluster which is completely managed by Google Cloud

- kubeadm – create a development cluster with a single master

Kubernetes is composed of many individual parts and you can do this manually or “the “hard way” using Kelsey Hightower’s infamous instructions.

kubectl get pods

Fetch the running containers (presented by the API Object Pods)

kubectl get all

Get all objects deployed

Add -n kube-system to also show Kubernetes system-level components which run as containers/Pods.

Nginx in 30 seconds

Nginx is a popular webserver and reverse-proxy:

Launch Nginx as a service on Docker Swarm:

$ docker service create --name nginx --publish 80:80 nginx:latest

Port 80 is automatically exposed on every node in the cluster through the service mesh.

Inspect, then delete:

$ docker service ls

$ docker service ps nginx

$ docker service inspect nginx

$ docker service rm nginx

Kubernetes:

$ kubectl run nginx --image nginx:latest --port=80

deployment "nginx" created

This creates a deployment and schedules a Pod on one of the nodes in the network. It’s not yet exposed outside the cluster.

You now have to pick between a LoadBalancer (only available on a cloud host), an IngressController (needs Nginx or Traefik installing separately) or a NodePort.

Here’s how to use a NodePort:

$ kubectl expose deployment/nginx --type="NodePort" --port 80

You can now access the deployment by finding its corresponding port on the Node.

$ kubectl get services

NAME CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S)

nginx 10.110.240.60 <nodes> 80:31359/TCP 18s

You can curl the container with the cluster-IP of 10.110.240.60 on port 80 – or use the NodePort and the Node’s IP i.e. 192.168.0.45:31359.

Inspect/delete:

$ kubectl describe deployment/nginx

$ kubectl get deployment

$ kubectl delete deployment/nginx

$ kubectl delete service/nginx

Networking

Docker Swarm’s networking model uses “overlay networks” by default which is a kind of Software Defined Network (SDN). Recent changes mean that the data plane and control plane can run over separate interfaces. New options are emerging for Docker Swarm including host networking and a Virtual-Machine (VM) specific networking option called “macvlan”. Additional networking drivers can be provided by vendors.

Read more here on Swarm networking.

Networking is “batteries not included” with Kubernetes – you need to make an educated decision on which third-party software to load into your cluster to provide networking. With Kelsey’s guide you can learn how to use host networking, but most people will use a Software Defined Network (SDN) such as: Weave Net, CoreOS Flannel or Nuage.

If you’re starting to learn Kubernetes or running it for development just pick Weave or Flannel. For production usage you will need to do your homework and look into whether you need to pay for “support” too.

API / integration

Docker Swarm’s API is made available through the moby/moby project and can be used to automate container orchestration. You also have everything available that the Docker CLI can do – which means building images too. Once vendored your builds time doesn’t increase significantly.

The Kubernetes project ships a Golang client on GitHub. It has been evolving for longer than Swarm’s which means you have to content with a complex set of namespaces and API objects and a much larger code catalog. With more power comes more of a learning curve. On an Intel i5 building the basic Golang example can take 1.5-2 minutes.

I’ve been able to use both APIs in the OpenFaaS project and for some side projects. They both work well, but be sure to “vendor” the dependencies before you start work.

Scale

I suspect a small percentage of Docker/Kubernetes users need to scale to huge numbers, but scaling up is a selling-point of an orchestration and clustering system.

I was unable to find any claims published on the maximum supported scale for Docker Swarm or EE. There were two community projects by Chanwit Kaewkasithat looked into this – Swarm2k and Swarm3k and they are relevant if you’re looking for massive scale.

The maximum/supported scale for Kubernetes is covered here and lists support in v1.8 for a 5000-node cluster. Note you can run more than one cluster separately if you have larger systems.

Migrating legacy apps

At the Open Source Summit in LA I spoke to a developer from TicketMaster who wanted to migrate his team’s .NET applications to Kubernetes, but felt the support (while functional) involved too many manual steps to get working. I’ve got first-hand experience of moving traditional apps over to Windows Containers with .NET 4.5 and IIS – the experience is relatively straight-forward with Docker and works well in Docker Swarm too. Docker EE is also offered for Windows Containers.

With Docker Swarm a multi-OS cluster is only ever a few command-line entries away as I explain in this use-case: Serverless functions on Windows and Linux made easy.

You can find out more in my Windows and .NET blog series.

Wrapping up

Many of us have heard statements like “Innovate or die: containers to the rescue” by ADP’s Chief Strategic Architect – Jim Ford.

The then-CTO Keith Fulton of ADP keynoted at Dockercon 2016 and said “Every company is a tech company right now – this is a race and there is no finish line.”

Cloud-native, container technology is important for staying relevant and being able to compete in this never-ending race. You may be wondering where to start and which orchestrator to pick?

My advice is: learn both.

Docker Swarm and Kubernetes both differ in many ways but have enough similarities that you can transfer across your learnings and make a decision about what is right for your team or project.

There may also be practical reasons to pick one or the other which won’t be apparent until you start moving forward and getting your hands dirty.

This needn’t be a heavy investment – I have a set of Docker and Kubernetes blog posts designed to take around 10-20 minutes each and they’re hands-on, so you are right where you need to be.

For Docker Swarm follow my 19-part series dating back to June 2016:

For Kubernetes

- I’d recommending starting with

kubeadmon a cloud host or withminikubeif you are running a Mac: - My learn-k8s series and master the basics in 10-15 minute chunks.

- Create a Kubernetes home-lab with Raspberry Pi